FLASH! In the news world, that word has an electric appeal, it means something "hot." It connotes special interest and speed.

In the world of photography too, "flash" represents something very special. It is a technique which has elevated the quality of much photographic work and has opened vast new possibilities.

Taking pictures by means of flash -- a sudden, in tense "explosion" of illumination -- is not strictly a modern development. Great-grandad's wedding picture might have been made while the photographer's assistant set off a blinding, smoky, smelly powder which scared everybody half to death.

The flash lamp -- which has largely superseded powder -- is, however, an achievement of quite recent years. And the skillful application of the flash method to many phases of photography has only begun to be appreciated.

It is now used even in daylight, while assuming broader use as the sole source of light or in combination with other types of artificial light. The opportunities it offers are limited only by the photographer's ingenuity.

Flash facilities place at your disposal a handy and highly concentrated light delivered in an exceedingly brief period --about 1/8 to 1/200 of a second.

The photoflash lamp--safe, clean, silent, simple-- has generally displaced powder-dangerous, dirty, noisy, inconvenient. Powder remains the less ex pensive form and is superior when extremely large areas are to be illuminated.

Early in the 1930's the flash lamp assumed an important place in news photography. In the ensuing years it has been widely adopted in nearly all fields of photography.

One "poof"-and the photoflash bulb has lived its life.

In shape and size it looks much like an ordinary electric light bulb. But it is filled with foil or wire or priming material. The foil, or wire, is made of magnesium or aluminum. The foil is sometimes shredded. The bulb also contains a fine wire filament. Air is replaced by oxygen and the bulb is then sealed.

The lamp is placed in front of a concave (bowl-shaped) reflector. (See figure 43 in chapter 3.)

In most flash lamps-- foil-filled or wire-filled current from a battery or other electrical source passes through the filament and ignites a small amount of priming material which coats the filament. The primer, in turn, ignites the foil or wire.

In the new SM and SF lamps, a much larger quantity of priming material is used and the wire or foil is omitted. Therefore, the flash is due entirely to the primer, which accounts for the high speed of these types.

Magnesium and aluminum foil or wire burn extremely rapidly in oxygen. An intense white flame is produced for about 1/100 to l/15 second. The period of full usable peak brilliance ranges from approximately 1/200 to 1/20 second.

Combustion is so fast that an explosive force is created, but the glass of the bulb is kept from shattering by a coating of lacquer. A cracked bulb is almost certain to burst when used. Therefore, some lamps are made with a spot which changes color on exposure to air that has entered through a crack. The color spot thus indicates that the lamp is no longer safe for use.

Because of the possibility of the bulb's exploding, the reflector should always be in place when a lamp is being used. The reflector, besides directing the light, serves as a protective shield for the photographer. For the same reason you should protect a person being photographed with the flash bulb less than 6 feet from his face. Hold a piece of film, Kodaloid, or like material in front of the lamp. That will prevent shattered glass from reaching the person with enough force to cause serious injury.

If a foil-type lamp is set off within a half-inch or so of another foil lamp, the heat of the first will ignite the second. It is possible to take advantage of this characteristic when you wish to use two or more bulbs to illuminate a scene but have facilities to connect only one to the power source. By the same token, special care must be taken in stowing or transporting foil lamps. Do not take them out of their paper wrappers until you are ready to use them. Wire-type lamps are easier to handle because they cannot be activated by contact with another lamp.

The glass of all flash lamps is extremely thin. Utmost caution is necessary to prevent cracking or breaking.

All flash lamps may be set off with current supplied by batteries delivering a minimum of three volts. Some lamps-such as the G.E. Nos. 22 and 5 may be used with a current as high as 125 volts. This can be done because the leads include a fusing material which will prevent the blowing of fuses in case of a short circuit. Lamps without this arrangement should not be used on high voltage.

Bulbs designed for low voltage are marked "For battery flashing only." Others are designated according to the voltage which can be employed, from 3 to 12 volts.

The drain on batteries simply for igniting the lamp is small. But most synchronizers used with flash lamps place a heavy drain on batteries. Therefore, batteries should be replaced frequently-every 100 or so exposures, or when the current tests below 7 amperes. Never depend on them after their expiration date has passed.

Temperatures affect battery efficiency. At 70F, the batteries are considered to be 100 percent effective, at 40 F. about 70 percent, at 0F. about 35 percent. When working in extreme low temperatures, you should arrange some means of heating the batteries and keeping them warm. Some increase in efficiency is obtained above 70 F., but this is of no importance to the photographer.

Several manufacturers produce flash lamps to different specifications to meet the varied requirements of photography. Lamps with a short peak of illumination--about 1/70 to 1/100 second--are designed primarily for use with synchronizers for between-the-lens shutters. One new lamp has a peak of 1/200 second and works only with a special synchronizer.

Lamps with a long peak of illumination-about 1/30 to 1/20 second-are intended for use with focal plane shutters. A shutter moving across the focal plane takes more time to expose the entire film than one which is between the lenses.

Lamps with high illumination values, but which may have a slight variation in flashing time are made for use with "open flash" (which will be ex plained shortly) or with show shutter speed, such as l/25 second.

Size varies considerably. Small and medium lamps are most popular because of their convenience in carrying.

Types of base also differ. The smallest lamps are fitted with a bayonet base, in which a pin slips into a slot or groove and snaps into place when turned. Other sizes have the standard screw base like an ordinary light bulb.

Manufacturers list the characteristics of each type of lamp. Here is a typical description-

Pause for a moment to look into those terms "lumen" and "lumen seconds." A lumen is a unit of light, a measure of light intensity. A lumen second is a measure of the quantity of light. Lumen seconds, taking into account both the intensity and duration of light, measure the total light output of a flash bulb.

Lumen seconds are not a measure of exposure. Generally you use only a part of the light from a flash lamp-at a speed of 1/200, perhaps 60 percent of the light. So, two lamps of the same lumen second rating might give you a difference in exposure, depending on how the intensity of their light is distributed.

Now, see how the typical information on a flash bulb is important in selecting the proper lamp and making the best use of it.

The total light in lumen seconds is significant in "open flash" work. Under this method, you open the camera shutter, then flash the lamp, and then close the shutter. Thus you utilize the entire light output of the lamp. And thus you need to know what the total light will be.

Two other points--the peak intensity above half peak in lumens, and the duration of the light above half peak--are vital, considered together, when the lamp is synchronized with the shutter.

Other data in the list are necessary, obviously, in determining whether the lamp is suitable with your equipment.

Certain lamps, you have noted, are made for use with synchronizers, others for "open flash" work. Time now to examine each of those processes separately.

You know the meaning of "synchronize." When two

things function together, when they are "in step," they are synchronized.

Synchro-flash photography means that the timing of the shutter and the lamp is coordinated. The shutter is opened and the bulb is ignited at the same instant by a mechanism called a synchronizer. It operates either mechanically or electrically, at speeds ranging from 1/50 to 1/1200 second.

These instruments come in a number of makes. They are so much alike that they will be considered in basic types rather than in specific models.

The synchronizer consists of a magnetic or mechanical tripper attached to the shutter and connected with a battery case. The case may be one made for use with standard flashlight batteries, accommodating two cells (3 volts) or three cells (4 ½ volts). Special cases for 9-volt batteries are available for some synchronizers. Voltage above 3 is necessary only when two or more flash lamps are used at one a time, with extensions directly from the synchronizer.

The battery case is usually attached to the camera. To the case is fastened a reflector of the proper size and shape, adjusted for the particular lamp being employed.

Most of the modern models have two or more electric outlets in the head of the battery case. One is for the connection to the shutter (in magnetic tripper models). The others are for attaching extensions for additional bulbs. A button switch, or the head of a cable release, is attached to the instrument for convenient operation.

Most synchronizers have a means of exactly adjusting the highest peak of light to the exact instant of the shutter's full opening.

The Mendelsohn, Abbey, Jacobson, Heiland "Sol," and Kodak Speedgun synchronizers are examples of the magnetic tripper type which taxes batteries heavily. Best results, therefore, are obtained by allowing time after each shot for the batteries to recover their full power. If shots are timed too close together, a lag is likely to appear in the flash, and the result is poor synchronization.

The Kalart is an example of the mechanical tripper type. It is far easier on the batteries because the current is used solely for igniting the lamp and not for opening the shutter.

Synchronizers mentioned so far are for use with between-the-lens shutters and the very small cameras with focal plane shutters, such as the Leica and Contax. Special synchronizers are needed with focal plane shutters in the larger cameras.

The built-in Folmer Graflex, Kalart Sistogun, and Smeaton Focal Plane synchronizers are of this special type. They are designed for use with long peak lamps, such as the G.E. 31 and Sylvania ZA, and with focal plane cameras of the 2-1/4 x 3-1/4, 3-1/4 x4-1/4, and 4 x 5 sizes.

The synchronizer will usually be adjusted for use with the camera assigned to you. If a new one is issued and has to be adjusted, or if one gets "out of tune," the manufacturer's instructions will explain how to make the correction.

How can you tell whether your synchronizer is performing accurately? Assuming that you do not have one of the mechanical or electrical devices made for this purpose, there are several tests which can be made easily with materials on hand in any laboratory.

One is adequate as an emergency expedient but is not recommended for any other purpose. Remove the back of the camera, Place the flash lamp in the synchronizer and hold it in front of the lens. Set the shutter speed at the highest to be used. Looking through the camera from the back, set off the lamp. If you can see the flash plainly through the lens, the synchronization can be considered fairly accurate.

A more satisfactory test involves taking a picture of the flash lamp. Extend the camera bellows to its fullest. Put a bulb in the synchronizer. Bring the

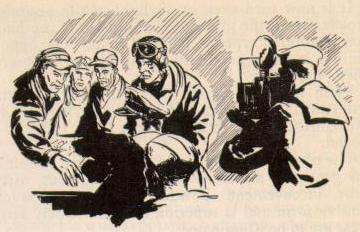

Figure 67-Flash lamps at different stages of intensity.

camera as close to the bulb as you can while retaining a sharp image. Set the lens at f/11 or f/16. Set the shutter at next to the fastest speed. Load the camera with a piece of Convira or Azo paper, #1 grade. Set off the synchronizer.

By the appearance of the image on the paper, you can determine whether the lamp is being ignited before, with, or after the shutter opening. Figure 67 illustrates how your picture might look and how you can judge it.

A indicates the appearance of a flash lamp when used by the open flash method. The shutter is open throughout the duration of the flash. Thus the picture shows almost the entire area of the bulb, the density indicating the most light. That particular illustration does not apply to the testing of a synchronizer. The other three do.

B, C, and D were taken with an exposure of 1/100 second. In B the shutter was open at the peak of the flash. That is perfect synchronization. In C the shutter opened a little too early-the light of the lamp had not reached its peak. In D the shutter opened late-the peak of the flash had passed.

A third way to test a synchronizer is simply to take a picture with it. Carefully measure the distance from your subject to the flash bulb. Set your shutter and aperture according to the guide number (see pages 292 to 294). Make the exposure, and develop the film. If the result is a negative of normal density, your apparatus is in good synchronization.

While you're checking your equipment, take a look at the position of the flash lamp and the reflector with relation to one another.

Certain reflectors are recommended for use with particular lamps. Properly paired, they will do their job correctly as a team-UNLESS the reflector has be come warped or shifted out of line. That can happen easily with constant handling of apparatus.

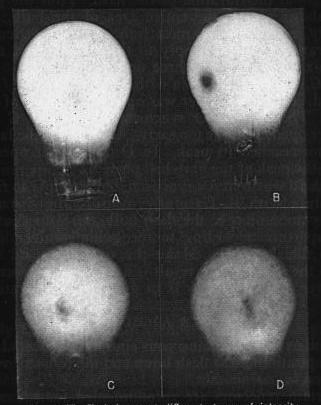

The spread of light will be at top efficiency only if the bulb is precisely the right distance from the reflector. How the rays of light are thus affected is depicted in figure 68. The correct focal point for the lamp is shown by the dot (F). In example A the position of the bulb is just right. The result is even

Figure 68-Effect of various positions of amp in reflector.

illumination. In B the lamp is too far forward and there is a hot spot" of light in front of the lamp. In C it is too far back-light is wasted by shooting to the sides. D shows the uneven illumination which results when the bulb is too high or low or off to one side. When a bulb is too big for the reflector, light intensity is lost as in E.

By far the greatest number of flash photographs are taken

with a single synchronized flash lamp. The use of two or more lamps is

an advanced technique which will be discussed in a little while. Right

now, concentrate on single flash.

A single lamp and synchronizer will give you ample control of lighting for most circumstances. It will enable you to use fast shutter speeds and small lens stops for depth of field that should be adequate for nearly all ordinary conditions.

Variation in lighting may be obtained by removing the synchronizer from the camera and holding it as far from the camera as the fittings will permit. But for most work, the instrument will be in its normal position attached to the camera.

The FACTOR OF GREATEST IMPORTANCE is the distance from the lamp to the subject. This distance determines all questions of exposure. The key to all the exposure information you need for single flash photography is contained in the following tables.

They give you guide numbers based upon different kinds of lamps and films. By a bit of easy figuring you can get your data on distance from subject and on lens stop.

GUIDE EXPOSURE NUMBERS FOR SYNCHRO-FLASH

1/200 Second

GENERAL ELECTRIC LAMPS (in polished reflector)

| Film Speed | For Between-the-Lens Shutters Shutters | For Focal Plane Shutters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #5 | #11 | #16A | #21 | #22 | #6* | #31** | |

| 6 | 48 | 53 | 58 | 63 | 78 | 24 | 28 |

| 12.5 | 68 | 75 | 80 | 87 | 110 | 33 | 40 |

| 25 | 95 | 105 | 115 | 125 | 155 | 47 | 55 |

| 50 | 135 | 150 | 160 | 175 | 220 | 65 | 80 |

| 100 | 190 | 210 | 225 | 245 | 310 | 95 | 110 |

| 200 | 270 | 300 | 320 | 350 | 440 | 130 | 160 |

SYLVANIA LAMPS (in polished reflector)

| Film Speed | Press 25 | #0 | Press 40 | #2 | Press 50 | #3 | #3X | FP-26* | #2A** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 40 | 33 | 40 | 60 | 48 | 70 | 65 | 24 | 40 |

| 12.5 | 55 | 45 | 55 | 80 | 65 | 100 | 90 | 33 | 55 |

| 25 | 80 | 65 | 80 | 120 | 95 | 140 | 130 | 47 | 80 |

| 50 | 110 | 90 | 110 | 160 | 180 | 200 | 180 | 65 | 110 |

| 100 | 160 | 130 | 160 | 240 | 190 | 280 | 260 | 95 | 160 |

| 200 | 220 | 180 | 220 | 320 | 260 | 400 | 360 | 130 | 220 |

For perfect synchronizaiion, a slightadjustment can be made when shifting from G.E. to Sylvania, or the reverse. The peak of most G.E. lamps used with between-the-lens shutters is about 21 milli seconds after the electric contact, of most Sylvania lamps about 20 milli-seconds.

FOR G.E. SM AND SYLVANIA SF LAMPS, exposure guide numbers are the same as (or the G.E. #31), but these two special fast lamps must be used only with a between-the-lens shutter.

How do you use the tables? Estimate or measure the distance from the lamp to the subject being photo graphed. Divide the guide number by the distance. The result is the f/stop to be set on your lens.

Here's an example. You are using panchromatie film with a rated speed

of 100, and a G.E. #22 lamp. The guide number is 310. Say the distance

from your lamp to your subject is 20 feet. Divide 310 by 20 and you get

15.5. So you set the lens diaphragm at the stop closest to that figure,

or f/16.

That will give you a well-exposed negative if-

First, the shutter is at 1/200 second (on which these tables are based).

Second, you are in a medium-size room (about 400 square feet

of floor space) with medium colored walls.

In circumstances other than those two, are the tables useless? Not at all. You can take varying conditions into account quite simply.

Suppose you are working outdoors, particularly at night, or in a room having dark walls or one with an area greatly exceeding 400 square feet. Do the same figuring and then OPEN THE LENS ONE STOP MORE.

In the example previously worked out, your exposure would be f/11 instead of f/16.

In very light-walled interiors, or in a room considerably less than 400 square feet in area, CLOSE THE LENS ONE STOP MORE. In the example, the correct exposure would be f/22 instead of f/16.

Now assume that you need an exposure shorter than 1/200. Just use a larger f/stop. Under the con ditions used in the previous examples, say you wanted the shutter at 1/400 instead of 1/200. You would OPEN THE LENS ONE STOP MORE. Therefore, the cor rect exposure would be f/11 in a "medium" room, f/8 in a dark or large room or outdoors, f/16 in a light or small room.

Reverse this calculating if you want the shutter at 1/100 instead of 1/200. CLOSE THE LENS ONE STOP MORE. Under the same example, that would give you f/22 in a "medium" room, f/16 in a dark or large room or outdoors, f/32 in a light or small room.

To clinch your understanding of how to use the tables, work out another problem. Use these facts- film speed 50, lamp Sylvania #3X, distance from lamp to subject 23 feet, shutter speed 1/400, outdoors at night. The solution--

The guide number for a Sylvania #3X and film rated 50 is shown in the table to be 180. Divide that by the distance, 23 feet, and you get 7.8. The lens stop closest to that figure is f/8, so that would be your basic exposure. But your shutter speed is double that on which the table is based. Opening the lens one stop changes your answer to f/S.6. Being outdoors, however, you must use the next larger stop. The final answer is f/4.

There has always been a tendency in single flash photography to overexpose badly, thus "blocking up" some areas of the subject. While this may be offset partially by underdeveloping to retain highlight detail, the fault can not be corrected that way.

One way to prevent this over-contrasty effect is to use reflectors to throw light into the shadows. An other is to place the subject near a light-colored wall to make full use of reflection from the wall into the shadows.

Still another way--and the best--is to use two or more flash lamps. Which brings you to the next subject

The use of two or more lamps in synchronization with each other and with the camera shutter is called multiflash. It gives complete control of light and effect. Almost any effect obtained by any other form of lighting can be reproduced by means of multiflash.

Figure 69-Photograph taken by multilfash. Note the depth provided by back-sidelighting.

Attainment of maximum quality requires study, experience and continual practice. But the results are well worth the effort.

Synchronizers operated on three-cell batteries (4 1/2 volts) may be fitted with two or three lamps on extension wires. All extensions combined should total not more than 80 feet.

Nine-volt batteries, used by such synchronizers as the Kalart, can be used safely with four lamps and high shutter speeds. With a greater number of lamps, they should be operated on currents of 24 to 125 volts, using a special relay placed in the wiring to the lamps.

This relay is closed by the battery current which at the same time trips the shutter. The heavier current passes through the closed relay to set off up to 30 lamps placed in series. The battery current opens the shutter, the heavy current ignites the bulbs. That arrangement prevents the heavy current from passing through the synchronizer with two serious consequences the synchronizer would be burned out and ruined, and the photographer undoubtedly would re ceive a severe electric shock.

The rather elaborate set-up of relay box and wires for use with a large number of lamps will probably never be necessary in your Navy work. But it is explained briefly to indicate the possibilities with flash.

You can't go around popping flash bulbs to experiment for the best lighting. There are two ways to tell how best to place your lights. One is by general good judgment. That calls for considerable experience. Until you acquire the experience necessary for close estimating, there's another method.

Use regular flood lamps, or other such lights, to obtain the desired illumination Locate your flash bulbs where you finally placed your test lights. Then use the flash lamps for the actual exposure.

In Navy work, however, you'll seldom have an opportunity to set up the lighting with flood lamps. Therefore, you'll have to learn the knack through practice with flood lights. Practice until you know the position and corresponding effect of each lamp under various arrangements. Then when you're pre paring to take a multiflash picture, you can locate your flash bulbs in minimum time for maximum effect.

Although each situation may call for different positioning of lights, one tip can be set down as gen erally good technique. One lamp should be at or near the camera angle to fill in the shadows. This should be on the OPPOSITE SIDE OF THE CAMERA from the highlight or main light source. In that way the shadow light will fill in the shadows completely. You will avoid the odd outlining of shadows that will otherwise occur.

EXPOSURE FOR MULTIFLASH

You have the exposure problem almost whipped to start with. Having learned how to determine the correct setting for single flash, you need to go only a little farther to find the right dope for multiflash.

The SAME TABLES GIVEN FOR SINGLE FLASH EXPOSURE are used.

One light, it was just noted, is placed at the camera angle (the line from camera to subject) to fill in the shadows. It should be placed at the distance from the subject that will give just the desired amount of de tail in the shadows.

The exposure with multiflash is determined by the distance from the subject to the nearest lamp. This will be the modeling light and it is the light that gives the highlights in the picture. Even if a third lamp is used to light the background, to bring out the full feeling of depth in the picture, the exposure will still remain the same. Care must be taken to place this third lamp at the proper distance from the back ground so that this part of the picture will be neither too dark nor too light.

You can be your own "synchronizer." Your hand and brain can take the place of an instrument. You can't be sure of the same perfection in tinting, but with lots of practice and a little luck you can get good flash pictures without a synchronizer.

Photography without automatic synchronization of shutter and flash lamp is referred to as open flash. The photographer opens the camera shutter, then sets off the flash, and finally closes the shutter-all in an instant.

Under this procedure, as remarked earlier, you take advantage of the full output of light from the bulb. With a synchronizer, on the other hand, the shutter is open for only a part of the split second dur ing which the lamp burns.

The open flash method can be employed with lamps or powder, and with single or multiple lamps.

During the intervals before and after the flash when the shutter is open, the film is, of course, being exposed to whatever light is present. Therefore, open flash should be employed INDOORS, OR, IF OUTDOORS, AT NIGHT.

Moderate amounts of action may be stopped, par ticularly when using the fairly fast flash lamps such as the 21 and 22, since the exposure is actually about 1/40 second.

In most cases of "open multiflash"--open flash with more than one bulb--the lamps are connected to one 110-volt electric circuit so that all may be set off at once. Or they may be fired simultaneously by bat teries and switches, each operated by a different man. Large street scenes may be done in this way if there is not too much movement present.

Where no action is taking place in the subject, the bulbs may be set off one by one.

Exposure for open flash, as related to the position of the lamp or lamps, is determined according to a table. For synchro-flash, the guide numbers were based upon the peak intensity of the flash and its duration above half peak. In open flash you are in terested solely in the total light output because the entire flash from beginning to end is utilized. Since a greater useful light is available, the exposure guide numbers are higher than for synchro-flash.

They are given in the following table, which is used in the same manner as the previous ones. Notice that with one exception the guide numbers for open flash apply also to synchro-flash at shutter speeds of 1/25 and 1/50 second. Notice too, that this table combines some of the Sylvinia and G.E. lamps in a single column-that, for example, the G.E. 6 and the Sylvania FP-26 have the same guide numbers.

GUIDE EXPOSURE NUMBERS FOR OPEN FLASH

(Or br synchronizer at 1/25 and 1/50 second)

G.E. ttS

Film[This table is incomplete at the moment]

Speed SYLVANIA- Press F? Ratrag 25 26 6 68 75 64 12.5 95 105 89 25 135 150 127 50 190 210 178 100 270 295 254 200 380 420 356 ~11 ~16A ~21 ~22 ~0 Press Press - 40 50 75 78 85 105 110 120 150 155 170 210 220 240 295 310 340 420 440 480 - ~31 - ~50~ SM~~ ~2 ~2A ~3 ~3X SF 110 128 98 170 135 35 155 180 138 242 190 50 220 255 195 340 270 70 310 360 275 484 380 100 440 510 390 680 140 140 620 720 550 968 760 200

Use open and 1/25 second only.

·~ 1/100 second also may be used.

In its infancy, flash photography was employed only in darkness or in the

absence of daylight. The process has grown up now. It associates not only

with other forms of artificial light but also with natural light.

A greater part of your Navy work will be done where daylight can and will have an important bear mg on the final results. That doesn't mean you'll have to put aside the flash method. On the contrary, a combination of natural light and flash light will produce a clarity and a dramatic quality which were not dreamed of a few years ago.

Under some conditions--as on gray days or in the early morning and late evening--the procedure is the same as for synchro-flash indoors or in darkness. Just recall that after figuring your exposure from the synchro-flash table, you use the next larger lens stop.

Even in bright sunlight, flash work offers distinctive possibilities. The sun does a pretty good job of illumination, but the sun doesn't always act as if it knows much about photography. Often, for exam ple, it throws a shadow exactly where you don't want a shadow. So the thing for you to do is to team up with the sun.

You can achieve the effect of multiflash by using sunlight for one source of illumination and a flash bulb for the second source. In nearly all cases the sun is used as the main source to illumine the high lights and the contour of the subject. The flash is used on the camera to give the desired detail in the shadows, bringing out the best balance between high lights and shadows.

This method affords you nearly limitless oppor tunities to obtain perfect reproductions of an entire subject almost without regard for the lighting con ditions of the moment.

Flash photography with sunlight is really as simple as straight flash photography. One more table is required as a shutter speed of 1/100 second is recommended to make full use of the sunlight and keep the distance from lamp to subject from being too great.

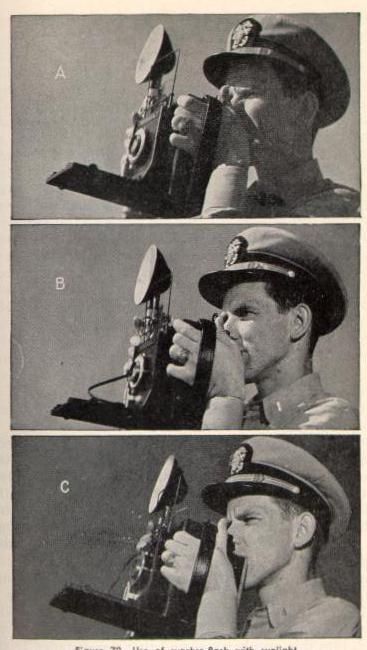

Figure 70 -- Use of synchro-flash with sunlight.

GUIDE EXPOSURE NUMBERS FOR SYNCHRO-FLASH WITH SUNLIGHT

1/100 Second

G.E. LAMPS (in polished reflectors)

| Film Speed Rating | For Between the Lens Shutters | ||

| #5 | #11 | #22 | |

| 25 | 115 | 125 | 190 |

| 50 | 160 | 180 | 270 |

| 100 | 225 | 255 | 380 |

| 200 | 315 | 355 | 530 |

| Film Speed Rating | For Between-the-Lens Shutters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #2 | Press 50 | #3 | #3x | |

| 25 | 160 | 130 | 200 | 180 |

| 50 | 230 | 190 | 280 | 230 |

| 100 | 320 | 270 | 400 | 360 |

| 200 | 445 | 380 | 570 | 560 |

SYLVANIA LAMPS (in polished reflectors)

| Film Speed Rating | For Between the Lens Shutters | ||

| *Press 25 | #0 | Press 40 | |

| 25 | 110 | 90 | 110 |

| 50 | 160 | 130 | 160 |

| 100 | 230 | 180 | 230 |

| 200 | 330 | 250 | 330 |

* In special Directed-flash Reflector.

How do you use the table? Determine the correct exposure for sunlight at a shutter speed of 1/100 second, WITHOUT REGARD FOR THE SHADOWS OF THE SUBJECT AND WITHOUT REGARD FOR THE FLASH LAMP.

Then find the distance from the subject at which you should place the particular flash lamp you are using.

Example: It's a bright, clear day. At a shutter speed of 1/100, you decide to use f/22 for the correct rendering of the highlights. The film you are using has a speed rating of 100 and you are going to use a G.E. #11 Lamp. This lamp and film combination has a guide number of 255. By dividing the f/stop, 22, into this number you find that the distance from the lamp to the subject should be about 11 feet. The result? Well, it will be about like the third picture in figure 70, the bottom one. Looks like the picture was made at night. What you want is something like you see in the middle picture. Here the sunlight is clearly the strongest, the sky has a good tone and the shadows have plenty of detail. The flash light is not so obvious. To get this effect you must do one of two things. You must move the flash lamp away from the subject until the distance is doubled, to 22 feet in this case, or you must reduce the intensity of the light from the lamp. Moving the flash lamp may not be possible unless you have suitable extensions, but the intensity of the lamp may be reduced in a very simple way. By placing two thicknesses of an ordinary hand kerchief over the lamp and its reflector you will re duce the intensity of the light by about 75 percent. By doubling the distance from the lamp to the subject you will reduce the intensity of the light to 25 percent of its original output, and by using the handkerchief over the lamp you also find the intensity about 25 per cent of the original. You can use either method.

That top picture in figure 70 shows you what this subject looks like when only sunlight is used.

Use of a handkerchief diffuses or softens the light. Not only will the shadows in the picture be illum inated but any shadows caused by the flash will be less distinct.

Constant practice will develop a degree of skill which will make the flash-with-sunlight technique one of your most effective tools in obtaining superior photographs under difficult conditions.

A flash lamp pierces darkness about the way a 16- inch gun salvo rends silence. The ordinary flash lamp, that is. There's one which is decidedly "un ordinary."

A photographer takes a flash picture in pitch darkness. Only a few feet away there is not the slightest hint of it. But what about the flash? There wasn't any. A flash picture with no flash? Well, for all practical purposes-yes.

Actually there was a flash. But it was made up almost entirely of infrared light, which is invisible. Yet the lamp illuminated the subject quite enough for a clear picture.

This is infrared flash photography or "blackout" photography. The special flash bulb is coated with a Lacquer which transmits a maximum of infrared rays while holding back nearly all the visible rays.

It must be used only with infrared film and in total or nearly total darkness. Slow shutter speed (1/25 to 1/50) and wide lens opening (f/4 to f/8) are required.

The phenomenon of blackout photography will work only at very short distances-usually 10 to 15 feet. But at close quarters it will produce a surpris ingly satisfactory photographic record.

This procedure might have numerous military uses. An example would be in taking a vital picture when a brilliant glare of white light would tip off your presence to the enemy. There are also less ominous circumstances which would make the use of the con ventional flash impractical or impossible.

Comparatively little information is yet available on the blackout flash. The following table, however, will give you a sound foundation for determining exposure.

G.E. #5R #22R

Frorn SYLVANIA Blackout 25 Blackout 2

Standard Infrared 55 6~~5

The low guide numbers indicate the short distances and large lens stops involved in infrared flash. With a #5B or Blackout 25 lamp the exposure at 15 feet would be f/3.5 (55 divided by 15 equals 3.6), at 10 feet f/5.6. With a #22R or Blackout 2, it would be f/4 to f/8.

With the slow shutter speeds, great care must be taken to prevent movement of the camera.